When we cannot see everything, we see nothing

90% of Environmental Impact in the Fashion Industry comes from Raw Materials and Certain Manufacturing Processes; conversely packaging and distribution are minor stakes representing together less than 10% of impact.

A study conducted by Glimpact revealed surprising insights about the driving forces behind environmental footprint across the fashion industry and dives into specific impact hotspots of popular products from brands including Patagonia, Reformation, H&M, Ralph Lauren, and AloYoga.

NEW YORK, NY (April 23rd, 2025) - On April 23rd Glimpact, the first platform for analyzing the overall systemic environmental impact of products and organizations, using their newly announced Global Impact Score tool (which will be launched in the coming weeks), released a study looking at the environmental impact of apparel and footwear products through product Life Cycle Assessments, which gives valuable insight on hotspots in the fashion industry and action leverage for brands. The Glimpact technology models environmental footprint assessments according to the new scientific framework of the PEF method. This method, which has been adopted by the EU as the universal method for measuring environmental footprint through the new regulation ESPR, measures environmental footprint comprehensively, considering 16 categories of impact across all life cycle stages from cradle to grave, including carbon emissions, water use, land use, etc., and radically changes the vision of environmental impact, revealing the true stakes of the ecological transition.

This Glimpact study assessed the environmental footprint of over 100 products to identify comprehensive trends in the fashion industry according to the Apparel & Footwear PEFCR version 2.0 which sets evaluation guidelines for apparel products assessed with the PEF method. To apply the initial findings of this study to specific cases, Glimpact’s newly released Global Impact Score tool was used, along with publicly available data, to evaluate the environmental impact of 6 different products currently for sale from Patagonia, Reformation, Alo Yoga, Ralph Lauren, and H&M.

Over 75% of environmental impact from apparel products is not traced to carbon emissions.

Looking only at climate change means ignoring three-fourths of a product’s environmental impact including fine particle emissions, fossil resource use, acidification and water use.

One key insight from this study is the different impacts a product has on the environment. With a comprehensive vision of environmental footprint defined by the PEF method, it is revealed that climate change, while important, is not always the main driver. In fact, for the more than 100 products evaluated, carbon footprint on average only accounted for 23% of the overall environmental footprint. This means over 75% of a product’s impact can be traced to other ecological indicators. Fine particle emissions is the largest contributor, accounting for about 35% of an apparel product’s impact on average, with fossil fuel use, acidification, and water use accounting for another 26% of overall impact. Understanding that the environmental crisis is more than just carbon emissions will ensure that as companies work to reduce their carbon footprint, they are aware of how their business impacts the environment on other fronts. Failure to do so risks shifting impact from one category to another unknowingly.

On average, 90% of apparel product impact comes from specific manufacturing processes and raw material production.

Of over 100 apparel products assessed, on average, packaging represents less than 2% of a product’s environmental footprint and distribution from factory to consumer is less than 5%.

In order to effectively reduce environmental impact, it is important to first identify where the largest areas of environmental impact, or “hotspots”, are coming from. To start, the entire lifecycle of a fashion product, from cradle to grave, must be considered. For fashion products, the full life cycle consists of the raw material stage, including the production of the raw materials themselves and any associated processing of those materials, the manufacturing stage, the product packaging, the distribution of the product to the consumer, the use of the product including washing and drying, and the product end-of-life.

When considering environmental impact over the course of a fashion product’s life cycle, it is apparent that the raw material and manufacturing life cycle stages are the hotspots for environmental impact. In fact, raw materials and manufacturing on average account for more than 90% of a fashion product’s environmental footprint. Raw material production on average accounts for 40% and various industrial processes account on average for 50% of an apparel product’s environmental impact. More specifically, raw material type and origin both play major roles in a fashion product’s impact. Similarly, certain manufacturing processes along the product supply chain such as dyeing/coloring heavily sway a product’s global footprint.

Equally important as discussing a fashion product’s environmental footprint hotspots is discussing the areas along the product life cycle that have relatively small impact. When viewed through a comprehensive lens, a fashion product’s packaging and distribution have a very small impact on the overall footprint. Of the apparel products assessed, on average, packaging is less than 2% of overall impact and distribution from factory to consumer, unless air freight is used, is typically less than 5% of overall impact. This means that for fashion brands who are working to be more environmentally friendly, sustainability initiatives around product packaging or distribution do not have the potential to make much of a real difference. If an apparel product is made halfway around the world, there is far more potential for impact reduction when you focus on its manufacturing and production conditions rather than on the distribution to the customer. It is important to note that air freight used during the distribution process has the potential to be a hotspot for an apparel product. Identification of the impact hotspots and understanding where impact is low relative to the life of a product ensures that actions taken by brands can have the maximum potential for impact reduction.

The same raw material impact varies widely depending on origin and production conditions.

Labels like “organic” do not necessarily correlate to positive environmental performance.

Now that raw material production has been identified as an impact hotspot, it is interesting to dive deeper into the environmental footprints of different fabrics to better understand how material choice informs the overall product footprint. Unsurprisingly, different materials have varying environmental impacts. Figure 1 illustrates the differences in only a handful of material choices, but the impact discrepancies can be large, even larger when considering materials that come from animals like leather, wool, or silk.

Figure 1. Environmental impact per kg of fabric made from different materials.¹

Figure 1 displays the global average impacts for 1 kg of these different material fabrics; however, even for one specific material, there can be a wide variation in environmental footprint that is determined by its origin and the farming or production practices.

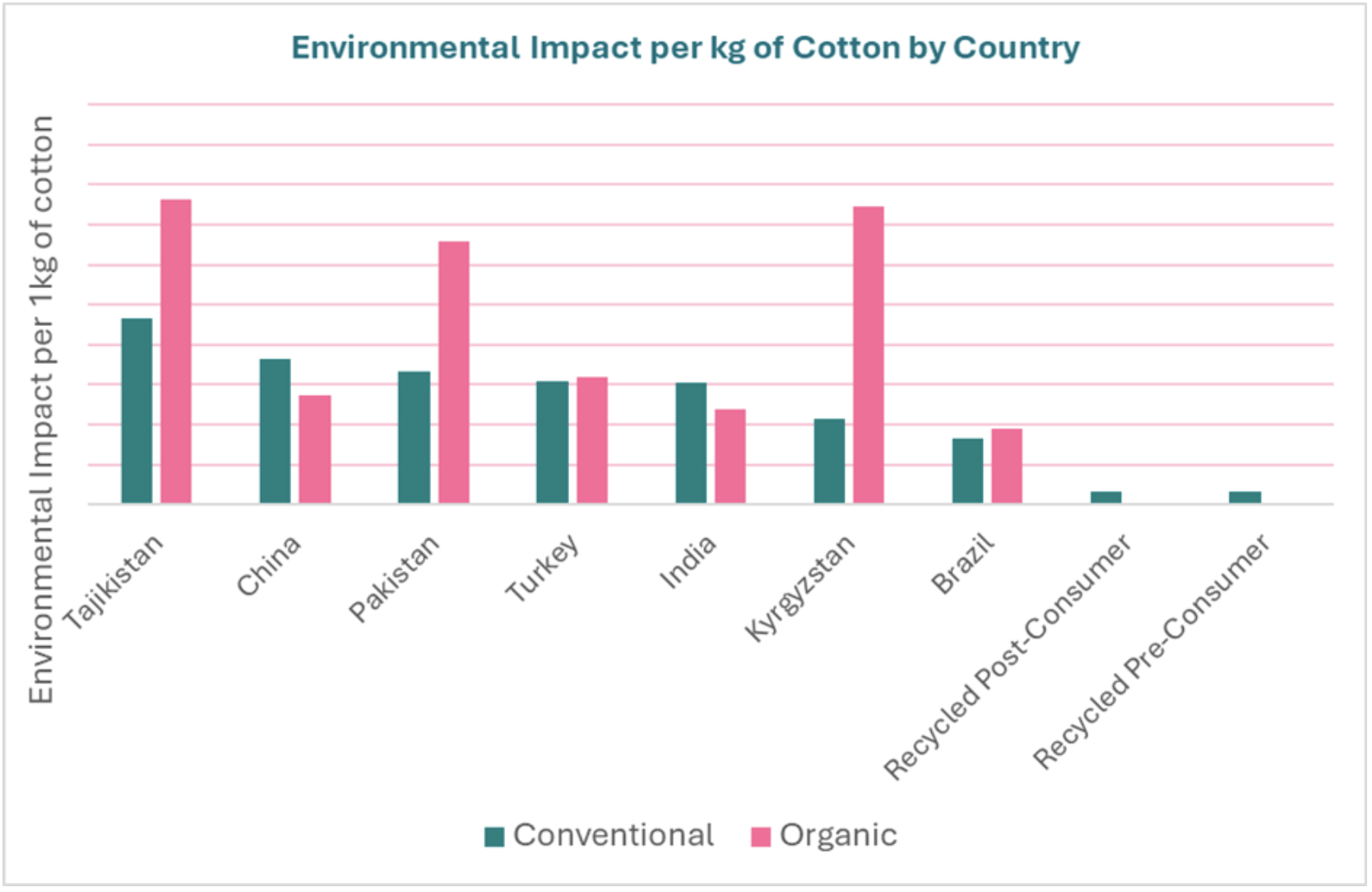

To zoom in on the importance of raw material and raw material origin, the example of cotton his taken. Just because a product is cotton does not mean that it is good or bad for the environment. There is a huge disparity in the environmental impact of cotton which varies based on numerous factors. This disparity is illustrated in figure 2, which depicts the environmental impact of 1kg of cotton from different sources and with different farming practices.

Figure 2. Environmental impact of conventional and organic cotton from various sources.

One striking takeaway from figure 2 is the variability of the cotton’s footprint depending on where it is grown. The origin of cotton can dramatically increase or decrease the environmental footprint of a product. This is largely due to climate conditions in these different regions and the suitability of that land to grow cotton. It is important to note that the datasets presented are generalized for each region, but even within each country or region, there is disparity among the impacts of different cottons. For example in China, which is a geographically diverse country, there are various regions that are more suitable or less suitable for growing cotton which is linked to water scarcity and soil quality and ultimately informs overall environmental footprint. Another interesting takeaway is the comparison in footprint between organic and conventional cottons. When measuring with a comprehensive footprint, it is revealed that organic cotton, which is grown without the use of synthetic chemical pesticides or fertilizers and is always safer for the health of the workers cultivating the crop, is not necessarily better for the environment than conventionally grown cotton. Cotton is a nutrient-hungry and water intensive crop, and non-synthetic pesticides and fertilizers still need to be used when growing cotton organically. Without the boost from synthetic fertilizers, yield per hectare may be lower, which corresponds to a higher impact per kg of cotton, meaning water, land, and/or natural fertilizer resource use may offset impact reduction from avoiding synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. This is especially true when cotton is grown in regions that are water scarce, have poor soil quality, or where cotton is not a native species. This underscores the importance of measuring environmental impact rather than making assumptions stemming from material labels to determine a product’s sustainability. Understanding the nuance of impact within one material category also opens the door for impact reduction opportunities by simply changing material sourcing or production practices as opposed to changing the material type entirely.

For over 100 apparel products, the dyeing process alone contributes anywhere from 15-60% of the product’s total impact.

The dyeing process, knitting process, and weaving process are all hotspots, and conversely product assembly processes represent less than 4% of total footprint.

Aside from the raw material itself, certain manufacturing processes have an outsized impact on the footprint of a product. Dyeing in particular was revealed to be an impact hotspot and therefore potential action leverage. For the apparel products assessed in the global study, dyeing was responsible for anywhere from 15% all the way up to 60% of the overall product impact. Dyeing is used in essentially all fashion products, and typically requires the use of chemicals, water, thermal energy, and electricity. There are numerous methods of dyeing, each with varying environmental footprints, as seen in figure 3.

Figure 3. Environmental impact of various textile dyeing processes.

The dyeing process, with all the associated chemicals, energy, and water, has the potential to have a large environmental impact for fashion products, but it does not have to. With the right dyeing process, a product’s total footprint can be greatly reduced. Just as dyeing can be identified as a hotspot, PEF assessments of apparel products also reveal that the assembly processes of an apparel product, including cutting and sewing, are not major contributors to environmental footprint. Identification of these processes with minimal stake helps to inform where impact reduction actions should be taken. That being established, with the knowledge of the limited contribution of distribution and assembly, it can be said that what a product is made from and how it is made are much stronger indicators of environmental performance than where the product is cut and sewn to be assembled.

On which action leverage can fashion industry players act?

Raw material origin, production techniques, and certain manufacturing processes like dyeing, knitting, or weaving together represent ~90% of the environmental impact of an apparel product, providing opportunities for key action leverage to significantly reduce footprint.

Identifying the different hotspots found in this study means identifying opportunities to reduce environmental impact. Raw material is typically a large hotspot for a product’s impact, but there is so much disparity in impact between different raw materials, and even for the same raw material but from different origins and with different production practices. Similarly, with processes like dyeing, weaving or knitting, which are usually large contributors to an apparel product’s footprint, their outsized environmental impact means that there is opportunity to reduce total footprint significantly. On the other hand, certain manufacturing processes including assembly can be identified as a non-hotspot. Understanding which processes along the manufacturing supply chain have large environmental impacts, and conversely which ones don’t, helps direct the focus of sustainability initiatives to action levers that have real potential. By comprehensively measuring impact and discovering the hotspots, action leverage for meaningful impact reduction becomes possible. With this context of the global fashion industry, this study will now examine real products currently sold by major brands, using publicly available information, to see how these insights can inform decision making.

Illustration of fashion industry findings with real products sold by Patagonia, Reformation, H&M, Alo Yoga, and Ralph Lauren

For one pair of Ralph Lauren pants, carbon emissions account for only 23% of the footprint

~50% of impact is attributed to particulate matter pollution, fossil resource use, and water use.

Looking beyond the comprehensive trends of the fashion industry, we can better understand the nuance of environmental impact and the effects of different action leverage by applying the insights gained from the global study to the product level. Glimpact assessed the environmental footprint of 6 products currently available from Reformation, Patagonia, H&M, Alo Yoga, and Ralph Lauren using the new Global Impact Score tool and publicly available product data.

The first key finding is revealed when looking at the environmental impact broken down by the different impact categories as defined by the PEF method. With a comprehensive view of environmental footprint, we can see that the carbon footprint of each product, while important, is not the only stake. Other impact categories including particulate matter pollution and fossil resource use, as seen in figure 4, account for a large share of the product’s global footprint.

Figure 4. Impact Category Breakdown for Ralph Lauren’s Straight Fit Linen-Cotton Pant

For these Ralph Lauren pants, the climate change impact represented 23% of total impact. For the 6 apparel products considered in this study, carbon emissions only account for 17-27% of the overall environmental footprint. Reinforcing the results of the comprehensive report, it was found with this study that particulate matter, fossil resource use, water use, and ocean acidification also contribute significantly to the impact of the products evaluated. This means if a brand is trying to be sustainable but is only considering carbon footprint, they risk missing about 75% of their overall environmental footprint. Even worse, measures taken by these brands to reduce their carbon footprint could unknowingly be futile due to increased impact in other categories.

97% of Alo Yoga Accolade Hoodie’s impact comes from manufacturing processes and materials

This product’s packaging and distribution account for less than 1% of impact, meaning these areas do not provide any real opportunities for impact reduction.

When taking a closer look at individual products assessed in this study, insights can be gleaned about where the environmental impact is coming from. For these 6 apparel products, when considering all stages of the product life cycle, the environmental impact is primarily coming from the raw material and manufacturing stages. These 2 stages accounted for more than 90% of the total environmental impact for each product evaluated. This takeaway reinforces the findings from the comprehensive report of the fashion industry at large and is displayed below for a specific Alo Yoga product in figure 5.

Figure 5. Impact breakdown by life cycle stage for Alo Yoga’s Accolade Hoodie

As expected, distribution and packaging played a small role in the evaluated product’s overall environmental footprint. In figure 5, we can see that for Alo Yoga’s Accolade Hoodie, the product distribution and packaging combined account for about 1.5% of the overall impact. For all 6 products, packaging and distribution combined never accounted for more than 3% of the overall environmental footprint. What this means is that if all the sustainable strategies for this product focus around changing the packaging design or optimizing the distribution scenarios, the most this product’s impact can be reduced is only 1.5%.

Patagonia’s Fitz Roy Icon Uprisal Hoody uses recycled materials and has a lower impact than Reformation’s Tessa Hoodie which uses organic cotton.

Reformation’s Tessa Hoodie’s made from 100% organic cotton had a higher impact compared toPatagonia’s hoody made entirely from recycled polyester and recycled cotton.

To compare the results of the different products evaluated in this study, the function of apparel products was taken into consideration. Since the function of such products is to be worn, the footprint of each product is compared by taking the impact per day of wear. This accounts for the useful lifetime of the product and factors like durability². The environmental impact is measured in micro-points, as defined by the PEF method. See figure 6 for the evaluation results of women’s sweatshirts from Reformation, Alo Yoga, and Patagonia assessed in this study.

Figure 6. Global environmental impact per day of wear for various women’s sweatshirts

For the women’s sweatshirts evaluated, Reformation’s Tessa Hoodie was found to be the most environmentally impactful, followed by Alo Yoga’s Accolade Hoodie, with Patagonia’s Fitz Roy Icon Uprisal Hoody being the least impactful for the environment. The impact for each product is largely being driven by the raw materials used. Here, the most environmentally friendly sweatshirt evaluated, Patagonia’s Fitz Roy Icon Uprisal Hoody, is made entirely from recycled materials. Meanwhile, Reformation’s sweatshirt, which is proudly touted as made from “100% organically grown cotton” performs worse than Alo Yoga’s sweatshirt which makes no sustainability claims. Reformation’s score may be surprising given the use of organic cotton, but as outlined above, the organic label is not an indicator of low environmental impact. To valorize claims around the environmental footprint of an organic fiber – in this case cotton – brands like Reformation must measure the true impact of their raw material to ensure their communication aligns with their actions.

Ralph Lauren’s Linen-Cotton Pant has a lower environmental impact than Patagonia’s Jeans.

Ralph Lauren’s use of majority linen outperforms Patagonia’s use of a cotton blend as the primary material.

Turning to a different product category, the Global Impact Score tool was also used to evaluate the environmental footprint of various men’s pants, with the results in figure 7.

Figure 7. Global environmental impact per day of wear for various men’s pants

Of the three pairs of men’s pants assessed, H&M’s Slim Fit Chinos were found to be the most environmentally impactful, followed by Patagonia’s Straight Fit Jeans, with Ralph Lauren’s Straight Fit Linen-Cotton Pant having the smallest environmental footprint. For these products, it is once again material makeup that is the differentiating factor, with dyeing process playing arole here as well. Ralph Lauren’s straight fit pant performs the best in large part thanks to its majority linen blend. When compared to other fibers used in the fashion industry, linen typically has lower impact since its parent plant (flax) is easy to grow. Patagonia and H&M have similar raw material makeups, being majority cotton with a small amount of spandex. However, Patagonia’s jeans have a lower impact than H&M’s Chino’s due to 35% of the cotton being recycled and from the lower impact foam-dyeing process used to color the fabric.

The environmental impact of Reformation’s Tessa Hoodie could be reduced by 40% by changing the cotton source.

The knowledge that raw material is a hotspot for this product allows for actionable insights to significantly reduce its environmental footprint.

Brands that want to be sustainable do have options available to them, but it’s important they first understand their environmental footprint comprehensively. With a global vision, one action lever that appears is raw material source. As mentioned above, the environmental impact of cotton varies greatly depending on where it is sourced. Taking the example of Reformation’s Tessa Hoodie, we can see in the below figure how different cotton sources can affect the overall footprint of a product.

Figure 8. Impact of Reformation’s Tessa Hoodie using cotton from different sources.

The potential for impact reduction through raw material is clear. By keeping the same primary material, cotton, but changing the sourcing of that cotton, this product’s footprint can be reduced by over 40%. Additionally, we can see here that if organic cotton is used, that isn’t enough to assume a product is better for the environment. The impact of that organic cotton must be measured to demonstrate that it has a smaller footprint, otherwise there is a risk of increasing a product’s impact on the environment.

Patagonia could reduce the impact of their Fitz Roy Icon Uprisal hoody by over 10% through changing their dyeing process.

Even for products with a low environmental footprint, there is room for impact reduction when the right hotspots are identified.

Another potential lever for action mentioned previously is the type of dyeing process used.With the myriad dyeing processes used in the apparel industry, there is great disparity in the environmental impact depending on how a product is dyed. Focusing on one Patagonia’s sweatshirt, we can see in figure 9 how a more environmentally friendly dyeing process can reduce this product’s overall impact.

Figure 9. Impact of Patagonia’s Fitz Roy Icon Uprisal Hoody with different dyeing processes.

Here, we can see how the impact of Patagonia’s Fitz Roy Icon Uprisal Hoody can be reduced by about 11% by only changing the way the material is dyed. Even though this product proved to be the most sustainable in comparison with the various sweatshirts, there are still opportunities to reduce the product’s impact further.

Sustainable action without measurement risks wasting money on low-impact initiatives.

With knowledge of environmental footprint, brands can act on real leverage in line with their practical and economic constraints.

Brands looking to reduce the environmental footprint of their products need to make sure they are looking in the right places. To avoid wasting time and resources are on low-impact measures, and to avoid the risk of greenwashing inadvertently, brands need to measure and understand their environmental footprint. Through this understanding, action levers are revealed and concrete changes can be made that reduce the environmental footprint of apparel products meaningfully and significantly. The opportunity to understand impact at this level will be available to all fashion brands with the launch of Global Impact Score, a free online tool that launches at the end of April.

About this study

The specific product assessments in this study were performed using the newly announced Global Impact Score, a free online tool specifically aimed at evaluating the environmental footprint of apparel products. Global Impact Score is available to both consumers and brand professionals alike, allowing all stakeholders the opportunity to understand the impact of apparel products through a life cycle assessment according to the PEF method. This study used the Global Impact Score tool to perform life cycle assessments according to the PEF method on the following products: Patagonia’s Fitz Icon Uprisal Hoody and Men’s Straight Fit Jeans, Reformation’s Tessa Hoodie, Alo Yoga’s Accolade Hoodie, Ralph Lauren’s Straight Fit Linen-Cotton Pant, and H&M’s Slim Fit Chinos. These products were evaluated using publicly available data, and assumptions based on similar products. With more specific product data, there is a possibility of additional eco-design action levers not discussed in this study being available to the brands. For a full list of the data used and assumptions made, see the table below.

The global industry insights were assessed using the full Glimpact platform. For more information on the datasets and calculation tool behind this study, please see the Global ImpactScore website.

¹ Figure 1 data shown for environmental impact of 1 kg of fabric for different materials assumes each material fiber is scoured, spun, sized, woven into fabric, and de-sized. If material origin is not specified, a global average data set was used.

² Durability is an important factor in environmental footprint and for eco-design. As defined by the PEF method, durability for apparel products is defined by various ISO tests for color fastness, tensile strength, tear strength, etc. While durability is an important action leverage for reducing environmental impact, this information was not publicly available for the products included in this study, therefore its effect on product environmental footprint and opportunity for impact reduction while important, is not mentioned further.

Products considered in this study:

Alo Yoga Accolade Hoodie

Reformation Tessa Hoodie

Patagonia Fitz Roy Icon Uprisal Hoody

Patagonia Men’s Straight Fit Jeans

H&M Slim Fit Chino’s

Ralph Lauren Straight Fit Linen-Cotton Pant

Product evaluation inputs and assumptions:

Please see below tables for all product evaluation inputs and assumptions.

*indicates required data is not publicly available so an assumption has been made. Assumptions taken are based on similar apparel products, and from Glimpact knowledge and expertise in the fashion industry.

**if a country location is unknown, a global average data set for the specific raw material or manufacturing process is used.

◊ If information availability is listed as "no", a default scenario defined by the PEF method is used to account for the impact of the relevant area.